Tanzania

- Joseph Bowman

- Apr 5, 2022

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 6, 2023

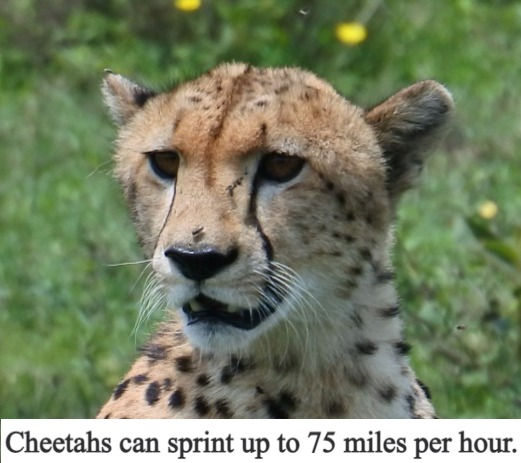

Lions, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas, and the various animals they eat are a fascinating mix of action and beauty, like Serena Williams or Tom Brady, except nobody takes it personal if somebody chases down and eats somebody else. Everybody more or less takes it in stride and moves on.

In mid December, about a week after my wife and I booked our trip to Tanzania and plunked down a considerable amount of nonrefundable money, the U.S. State Department slapped a level 4, code red, "Do Not Travel" trip advisory on Tanzania. The State Department deemed Tanzania too dangerous for U.S. travelers because of the COVID-19 omicron variant, terrorism, and crime. A decision had to be made. If we cancelled the trip, we might get about half of our money back and then only if we successfully haggled with our travel insurance company. That meant losing at least $9,000 if we were lucky. We gritted our teeth and decided to take our chances.

Our plane landed at Kilimanjaro International Airport. The next day, we met our guide, Philip, a certified safari guide with Nomad Tanzania, one of many safari companies in Tanzania. Philip would guide us through our first six days exploring Tarangire National Park and Ngorongoro Crater. We would then catch a small plane to the southern Serengeti where Allan, a certified guide with Sanctuary Kusini, would spend the next five days guiding and, in particular, helping us find the beginning of the annual wildebeest and zebra migration north across the Mara River and into Kenya where the animals would find greener, fresher grazing. Tarangire, Ngorongoro Crater, and the southern Serengeti are in northern Tanzania, just south of the Kenyan border.

On our first night in Tarangire I woke to the sound of a truck's engine idling just outside our tent. I was irritated that camp staff would be working nearby with a truck at such an odd hour. As I listened, I realized the sound wasn't an idling truck, it was a purring cat - a big cat. I laid frozen in bed wondering if I had closed and locked the door to the outdoor shower. Apparently I did as we survived the night. The next morning while walking to breakfast at the main camp, the Maasai warrior who provided security for the camp cheerfully asked if I heard the lions outside my tent during the night. "Yes! I heard." The warrior's only weapon was a spear.

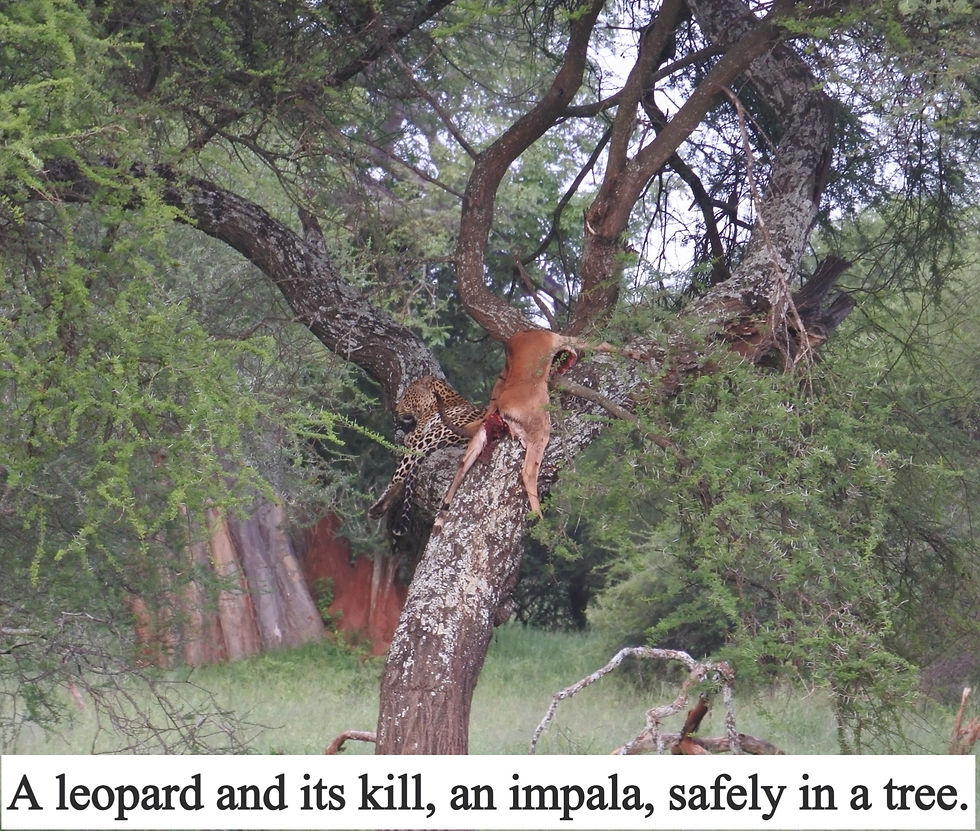

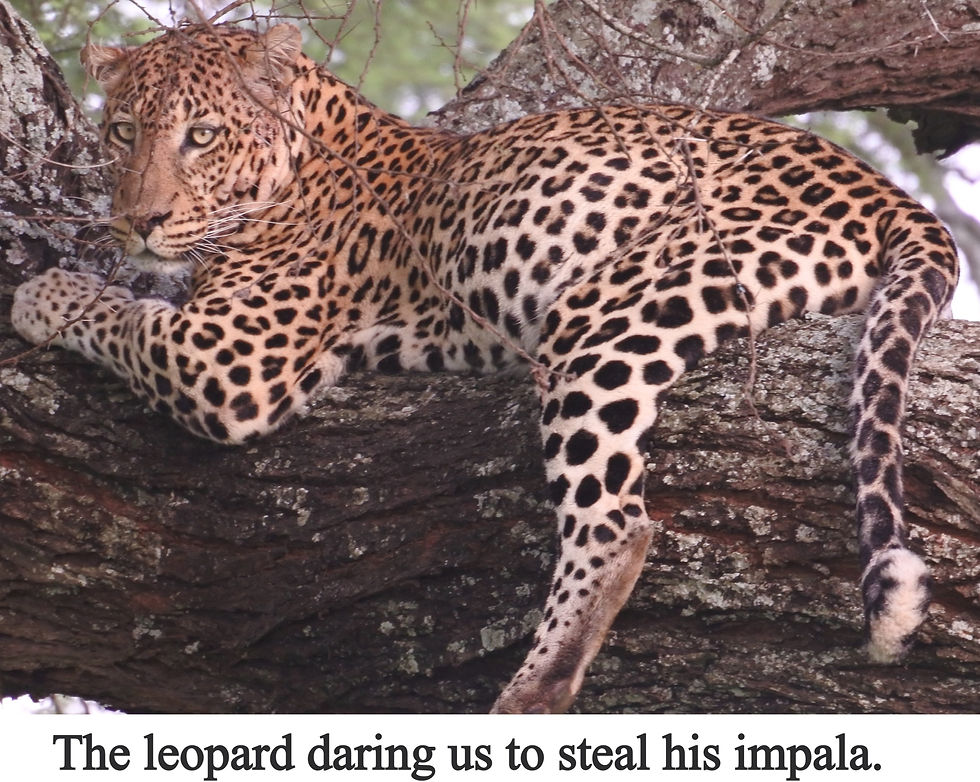

An hour later, during the first safari drive of the day, Philip spotted what looked like a dead impala in a tree about two hundred yards away. A leopard had killed the impala during the night and dragged it twenty feet up the tree, out of reach of hungry scavengers. Leopards are remarkably strong animals, as evidenced by the dead impala, which outweighed its killer by at least 75 pounds. As we slowly approached the leopard, it turned and made eye contact with me, certain I wanted to steal its impala. "No worries leopard, I just want to take your picture."

As we left Tarangire National Park on our way to Ngorongoro Crater, a troop of about 100 baboons came marching down the road ahead of us, requiring Philip to stop the Land Cruiser and wait for them to pass. Baboons are menacing looking primates, with their long dog-like faces, enormous fangs, and menacing expression. Philip warned me to stay in the vehicle as they passed by, saying that they would "butcher" me if I got out of the vehicle.

Baboons are omnivores, meaning they eat both meat and vegetation. Any predator that picks a fight with a baboon will find itself in a death struggle with a half dozen or more of these powerful, highly intelligent primates. As a result, baboons are rarely attacked by any of the big cats. As I watched the troop make its way past our stopped vehicle, I noticed a baby baboon riding on its mother's back. The baby was screaming, as babies will do. The mother, in a moment of rage, swung her right arm around and knocked the baby off, causing the baby to scream and screech even louder. The mother reached around, picked the baby up and hugged it gently until it calmed down. Then she returned the baby to her back, and marched on, all the while watching me with a menacing expression.

Ngorongoro Crater, home to virtually every creature Africa has to offer, was formed about three million years ago when an enormous volcano exploded. The Crater floor, covering about 100 square miles, is a vast grassland with occasional lakes and wooded areas. While touring the Crater in an open vehicle, one can simultaneously see elephants, African buffalos, cheetahs, hippopotamus, rhinoceros, ostriches, and every other African beast grazing and hunting.

The grey crowned crane is probably the most delightful creature in the Crater. A monogamous bird, it chooses its only mate for life. The birds will actually gather together to celebrate the wedding of two chicks, who will dance for their audience before flying away to begin their lives as a couple. If one dies, the other will pass away within a couple of weeks.

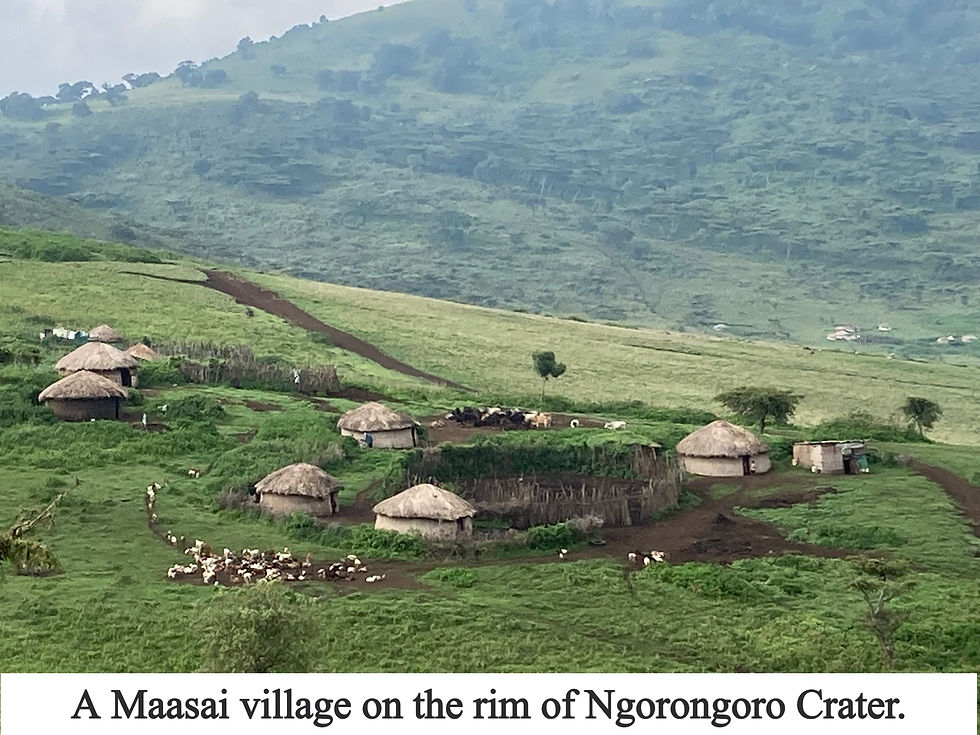

Ngorongoro Crater is also part of the ancestral territory of Maasai nomads, who have wandered the Crater and the adjacent Serengeti, following their cattle herds, across northern Tanzania and southern Kenya for many years. Maasai are the only people who may legally cross the Tanzanian border into Kenya and back without regard to legalistic formalities, such as passports.

Maasai adhere to strict cultural rules that to many outsiders seem primtive. They live in small camps composed of a boma, which is a central corral for their cattle, and that is surrounded by their dwelling huts constructed of tree branches, cow dung, and thatched roofs. Each hut contains a stall so they can bring a cow inside to help keep the place warm, along with an open fire in the middle of the dirt floor. Maasai don't allow their children to attend school. But, they produce handicrafts, including intricate bead jewelry. They have strong communal mores, and they can start a fire in a matter of minutes by rubbing pieces of wood together. Most impotant, their wardrobe is fab!

Predictably, this interesting culture is threatened by progress. Tanzanian authorities want to restrict the Maasais' nomadic territories, claiming that their cattle herds overgraze the Serengeti grassland, and that the Maasai harvest too many of the few trees on the Serengeti to build their bomas and little huts. Thus, the authorities reason, Maasai are a threat to the environment. The government is also urging the Maasai to send their children to school where, the Maasai fear, their unique language and cultural identities will almost certainly be weakened or eliminated altogether. Maybe these government initiatives will help the Maasai assimilate, and perhaps they should, but the world will be sorry when they are gone.

After a couple of days on the Serengeti, Allan found a herd of 25 to 30 thousand wildebeests and zebras, including their newborn calves and colts, forming and starting their trek to join the massive migration of one and a half million animals making their way to the northern Serengeti in Kenya. The low rumbling of their hooves reminded me of the never ending sound of an ocean. Indeed, the animals moved together like a tide of life. Our safari ended the next morning.

Before flying home, we spent a few days on the beach in Zanzibar. We also spent a day in Stone Town, the old town section of Zanzibar City, to visit the slave museum and walk around the markets and narrow streets that weave through the ancient neighborhood. At one point, a man sitting on a stoop spotted the colorful, knitted bag my wife was carrying and asked me, “Is it Ethiopian?” I told him I thought it Egyptian, because that’s where she bought it years earlier. His expression was one of doubt. Maybe he was correct.

We never got COVID-19, we never got kidnapped by terrorists, and we were never mugged. We had a remarkably good time in Tanzania.

THANKS FOR READING!

Pat and I booked our photo safari through Extraordinary Journeys (www.extraordinaryjourneys.com).

Contact: Pearl Jurist-Schoen at pearl@ejafrica.com.

More photographs follow:

Maasai boys work to start a fire with soft wood, hard wood, and friction.

They've got a spark.

Success!

Lion cubs on the Serengeti playing King of the Hill.

Zebras in the Ngorongoro Crater.

A wildebeest running to catch its herd.

The annual wildebeest and zebra migration begins in the southern Seregeti and moves north into Kenya where there will be greener grazing as the season changes. This herd of twenty to thirty thousand will join the migration of over a million wildebeests and about four hundred thousand zebras.

A large troop of baboons marching down the road toward our vehicle.

A Maasai village as seen from the road leaving the Ngorongoro Crater. In this photograph, you can clearly see the central cattle corral, surrounded by the Maasais' residential huts.

A lone acacia tree on the Serengeti. Local guides use this particular tree as a

landmark when navigating on the Serengeti.

Morning coffee on the Serengeti with Allan, our guide. The Toyota Land Cruiser, pictured here, has replaced the Land Rover as the preferred vehicle for the majority of guides. Land Cruisers are manufactured in Japan, then sent to a plant near Arusha, Tanzania where they are modified for use on photo safaris.

Joe B. this is so amazing. Thank you for sharing!